Rocio Rodriguez

CURRICULUM

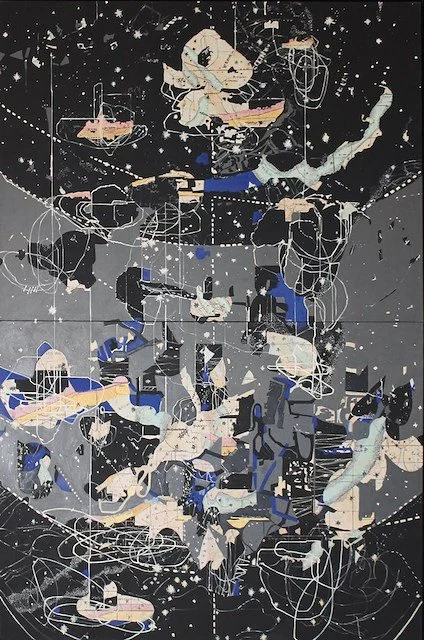

In an artist’s statement regarding Worlds upon Worlds, Rodriguez writes:

I want to express the beauty that connects art and science [...the work] is a metaphorical map that attempts to express that yes, we are cosmic dust, yet, within this universe, we have a place–as does every other planet and star. In that is the mystery of our existence.

This statement effectively encapsulates one view on what we might call the modern “existential” predicament par excellence: natural science reveals a universe of such staggering vastness in time and space that it would seem to make us, individuals and the entire human world, completely insignificant. How might we respond to this situation, characterized by Hannah Arendt as “modern world alienation” entailing a “twofold flight from the earth into the universe and from the world into the self…” (The Human Condition, 6)? For some, the answer has been to resign ourselves to meaninglessness. Others have renewed a commitment to older religious visions that grant us a place of significance in the cosmos, perhaps by understanding old accounts of Creation in a metaphorical sense. Still others have searched within the human experience itself for a new grounding, a solid point, for meaning in a seemingly meaningless cosmos. Writing at the end of the 18th century, Immanuel Kant (both a philosopher and astronomer) famously ends his Critique of Practical Reason with the following passage (perhaps the source of Rodriguez’s title “worlds upon worlds”):

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and the more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within. I have not to search for them and conjecture them as though they were veiled in darkness or were in the transcendent region beyond my horizon; I see them before me and connect them directly with the consciousness of my existence. The former begins from the place I occupy in the external world of sense, and enlarges my connection therein to an unbounded extent with worlds upon worlds and systems of systems, and moreover into limitless times of their periodic motion, its beginning and continuance. The second begins from my invisible self, my personality, and exhibits me in a world which has true infinity, but which is traceable only by the understanding, and with which I discern that I am not in a merely contingent but in a universal and necessary connection, as I am also thereby with all those visible worlds. The former view of a countless multitude of worlds annihilates as it were my importance as an animal creature, which after it has been for a short time provided with vital power, one knows not how, must again give back the matter of which it was formed to the planet it inhabits (a mere speck in the universe). The second, on the contrary, infinitely elevates my worth as an intelligence by my personality, in which the moral law reveals to me a life independent of animality and even of the whole sensible world, at least so far as may be inferred from the destination assigned to my existence by this law, a destination not restricted to conditions and limits of this life, but reaching into the infinite.

Kant believes he has proved what Rodriguez asserts her art is also showing us – that despite the annihilating vastness we see above us, we have “a place,” because each of us has, simply by virtue of being what we are, access to a timeless moral universe which is the source of all meaning (and, for Kant, the only subjective basis of religious faith). Later philosophers have differed greatly from Kant on this point, but are arguably all working within this framework. If the world as it presents itself to the natural sciences can no longer offer us a meaningful “place,” how can we look within to find this source of meaning and recognize ourselves as more than mere specks of dust?

Rodriguez seems to imply that her painting is more than a mere hopeful assertion of such a standpoint, however, and that “beauty” makes a bridge between art and science. There is something, perhaps, about the experience of beauty that gives us assurance that, although human beings are “cosmic dust,” we “have a place” within the universe that astronomy unfolds for us. Our experience of an artwork (in this case, pictures of the objectively modeled night sky made abstract and “metaphorical” and thereby into a comprehensible home for human beings) might be a moment which achieves by other means what a philosophical articulation like Kant’s attempts to demonstrate.

Yet philosophy at least aims for a certainty that, in its own domain, parallels the certainty of empirical scientific investigation (indeed, astronomy and geometry have often been a model for philosophical systemizations). The artist’s path, on the other hand, involves us in all of the ambiguities of interpretation that plague aesthetics. Is Rodriguez merely giving us an illustration, however beautiful, of an unprovable assertion, a kind of “aesthetic faith”? Or could it be that a successful presentation of beauty is, by definition, giving us a certainty that also parallels that of the natural sciences?

Writing in the aftermath of the 1957 launch of Sputnik-1, the first artificial satellite, Hannah Arendt remarked:

The trouble concerns the fact that the ‘truths’ of the modern scientific world view, though they can be demonstrated in mathematical formulas and proved technologically, no longer lend themselves to normal expression in speech and thought [...] But it could be that we, who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do (The Human Condition, p. 3).

Arendt depicts a situation in which the human capacity for expression has been exceeded by our capacity for action. She suggests that while we have the power to launch a satellite or look into the universe, this very capacity may have removed from us our capacity to thoughtfully articulate these things, or perhaps any things. And it would seem that for Arendt the efforts of past philosophers or ancient religious teachings cannot be called upon to simply put to rest this trouble.

The question raised by Rodriguez’s paintings, then, might be: does visual art have the ability to make “thinkable” and “speakable” the revelations of natural science and the technological powers these have unleashed? If so, how would it do so, and what relationship would such art have to the scientific domains from which it draws its subjects? Rodriguez’s works are particularly relevant here, because they depict the night sky – something that is both an eternal companion to the human species, yet also the most poignant symbol for us of our homelessness amid what may be an inhospitable and frighteningly vast universe, which since Galileo has been “delivered to human cognition ‘with the certainty of sense perception’” (Arendt, p. 261).

At stake here, therefore, are the nature and limits of a threefold relationship: between the nature revealed by science but “invisible” to ordinary human perception, the human world we think we meaningfully inhabit, and artistic creation. Again, astronomy provides a special look into this relationship since its objects are both “visible” (the night sky) and “invisible” (the processes described by astronomical science and physics; the universe as a whole). The question is: can artworks, like those of Rodriguez, provide any kind of “grasp” of the invisible processes underpinning the visible or of the “true visible” beyond our ordinary sensible perception?

Of course, one should rule out in advance any notion of art somehow “transmitting” mathematical description of natural processes into the brain of its viewers by some aesthetic shortcut. On the other hand, there are certainly enough suggestive remarks about immediate, intuitive, in-advance apprehension of the “results” of mathematical articulation in the history of natural science to make us wonder. Looking at paintings will not provide a shortcut to the particular type of mastery that scientist possesses – but, if there is indeed a common object in question here (e.g., the motions of the heavens), then perhaps it is a question of approximation: how close can the artist come to showing us whatever the great astronomer thought at the “eureka” moment, if such there was?

Yet this is not simply a matter of art giving us a summary or encapsulation of our uneasy sense of the world provided by natural science – on the contrary, it would be seem that the better informed we are about the materials of – in this case, astronomy, – the more the depictions, and the depicted, can mean to us. Does the given object (the night sky) stand for both an object of mathematically-articulable scientific truth, and, over this or behind it, “something else,” given to, for example, the vision of the artist? Can the sharpening of our astronomical gaze via objective understanding also provide a path to “thinking” and “speaking” the truth insofar as this is embodied in beautiful art?

Deeper into the Works

Rodriguez’s work’s abstraction recalls the earliest depictions of the night sky. One work in particular provides interesting comparisons. The Nebra sky disc was discovered at a Bronze Age site in Germany in 1999, ironically by two amateur collectors illegally hunting for artifacts. The Nebra disk is considered to be among the very earliest depictions of identifiable astronomical phenomena, including the Pleiades. Various explanations of its purpose have been advanced, but in any case the disk clearly represents a remarkable capturing of cosmic immensity by human art. While there are a number of earlier artifacts which seem to depict astronomical objects, these are either subject to ambiguities of interpretation or only show single objects (e.g., petroglyphs which may show supernovae). In the Nebra disk we see the duality inherent in these sorts of artifacts: there is both an attempt to comprehend the cosmos as an objective phenomenon, yet also an effort to give an aesthetic articulation of this overwhelming immensity in the palpably beautiful materials of bronze and gold. Possible uses of the disk include recording the solar and lunar cycle; so here we see an imminently practical purpose, keyed to the regularity and predictability of observable astronomical movements, yet an artistic object that combines the darkness of the sky (the now patinated deep-green bronze, which would have been a dark copper color when made) with the shimmering gold of the depicted objects. The golden objects are knowable, predictable; the verdigris behind them is the vast dark behind. While in ancient times this dark may have been perceived as, say, a materially comprehensible sphere of a size at least imaginable in human terms, it was nevertheless dark. For us, confronted with the “incomprehensible” vastness of space given to us by the modern scientific understanding, this bronze background darkness takes on a different, more unsettling significance.

Without undue speculation about the beliefs of the Nebra disk’s makers, we can assume that these people’s world was one in which, as in most pre-modern societies, there is a “place” for human beings and a shared understanding about the nature of this place. The sky disk may have represented a heavenly parallel to the rhythmic, comprehensible regularity that governed agricultural or other natural cycles, or perhaps keyed to ritual calendars – or seasonal cycles of warfare. It is possible, then, that the comforting prospect Rodriguez intends her art to embody – that there is a place for us in this universe – is a kind of updating of the role Nebra disk played in its society – bringing the immense and the threatening “down to earth.”

The problem raised by Arendt and others is that modern “world alienation” is not just a matter of the size of the universe, or the decentering of Earth by Copernicus and his successors, but a novel worldview that “considers the nature of the earth from the viewpoint of the universe” (The Human Condition, p. 268). We do not simply parallel in art the rhythms of our lives or of natural cycles with the observable rhythms of heavenly bodies – we now understand the “how” of these cosmic motions in the same terms by which we understand everything else; or, more properly, the understanding of the unseen forces that govern the natural world, first articulated (at least in part) in the context of astronomy, comes “down to the earth” and changes the basis of our entire worldview, our standpoint, and our understanding of ourselves.

From this point of view, it would have been no great thing to explain to a premodern person – the makers of the Nebra disk – that the worlds they saw in the night sky were actually far beyond any imaginable human scale in size and distance. They might very well have understood this, and yet gone on as before – perhaps further humbled but still understanding themselves to have a place in relation to this quantitatively expanded universe. And after all, we do not know how far the imaginations of past peoples’ might have penetrated into the objective immensities of time and space we now take for granted as empirical facts.

The problem then is far greater than simply saying human self-centeredness has been chastened by the revelations of astronomy (among other sciences). Many popularizers of the scientific worldview today celebrate this state of affairs, suggesting, for example, that understanding ourselves as specks of dust on a speck of dust might relativize our differences and thereby bring about desirable social or political ends.

Rodriguez’s painting Night Sky takes up some of these problems by depicting a more concrete and topical subject: the night sky above a battlefield of the Second Iraq War. Here, the infinity of the night sky stands above the very finite reality of human death in warfare. While to some extent a straightforward representation with elements of abstraction (particularly in the sky, which strongly resembles in its composition and coloring Worlds Upon Worlds), Night Sky connects the vision of the other painting more directly to human historical concerns. The question here relates to those things which often give a sense of meaning, place, or significance to modern people: nations, politics, wars. These things are often seen as scenes in which matters of the deepest moral or human significance are played out – human rights, political reforms or revolutions, or the notion of progress to a better material state. Night Sky raises the question: should we understand the juxtaposition of these scenes (the concretely human and historical with the chaotic order of the astronomical vista) as reducing the significance of these human events against the universal backdrop? On the other hand, should this be seen as increasing the significance of human events by putting them into a continuum with the eternal?

Conclusion

One element of the science of astronomy we can connect most directly to Rodriguez’s painting is its foundation in the practice of stargazing. Even without training in the principles of astronomy or access to sophisticated equipment, a student of the night sky can learn the shapes of the constellations and major visible objects with the naked eye or the aid of portable instruments. Although the constellations are necessarily only conventional, the stargazer begins to form a direct and experiential connection with and knowledge of the night sky as a concrete and immediate phenomenon. Arguably, this kind of practice can intensify the sense of wonder and the apprehension of beauty that nearly every person has experienced under the stars. It may be that paintings like Rodriguez’s provide an encapsulation of this experience by containing this beauty within the structure of painting on canvas. In the experience of both nature and human art, we see a visible beauty.

Yet, we can infer from her statement that Rodriguez aims at more: to give us through this beautiful articulation of one of the prime objects of natural science a reconnecting to the sense of the meaningfulness of life that we moderns may feel that we are missing on account of natural science itself. Indeed, even if we called such works – or pleasurable visions of the sky – an aid or inspiration to greater understanding of astronomical science, they could never replace the work of scientific understanding with knowledge gained from direct intuition. Yet perhaps they can help us to give a meaningful place to that knowledge in our lives and understand it otherwise than as a source of “modern world alienation.”

Questions for Discussion

Reflect on the claims made by figures like Hannah Arendt that we live in a condition of “modern world alienation.” Does it strike you as true that the modern scientific worldview deprives us of a meaningful place in the world? Relate this claim to your own religious or other beliefs about the place of human beings in the universe.

Relate some experiences you have had with the night sky. What feelings or thoughts have been produced by these experiences? If you are from an urban area, have you ever seen the night sky in a less populated place with less light pollution?

How do you understand the word “abstraction” with respect to art? In general?

Consider Rodriguez’s claim that “we have a place.” Does this strike you as true? Do you feel that her paintings as seen here confirm this claim?

Consider the question of “significance.” What does this term mean to you? In Night Sky, how is the significance of the dead soldier impacted by the starscape above him?

Discuss any experiences you have with the science of astronomy. What impact, if any, do Rodriguez’s painting have on your understanding of these experiences?

Rocio Rodriguez: Astronomy and the Human Condition

By Andrew Vlcek

Discussion and Research Questions

Resources

Resources

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Kant, Immanuel. Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason and Other Works on the Theory of Ethics. Translated by Thomas Kingsmill Abbott, 4th revised ed., Kongmans, Green and Co., 1889.

Lobell, Jarrett A. “The Nebra Sky Disc.” Archaeology, May-June 2019, https://archaeology.org/issues/may-june-2019/collection/maps-germany-nebra-sky-disc/.

Snow, C.P. The Two Cultures: The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1959, https://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs_5110/snow_1959.pdf.

“Worlds upon Worlds.” Permanent Collection of Agnes Scott College, 2024, https://daltongallery.catalogaccess.com/objects/228.